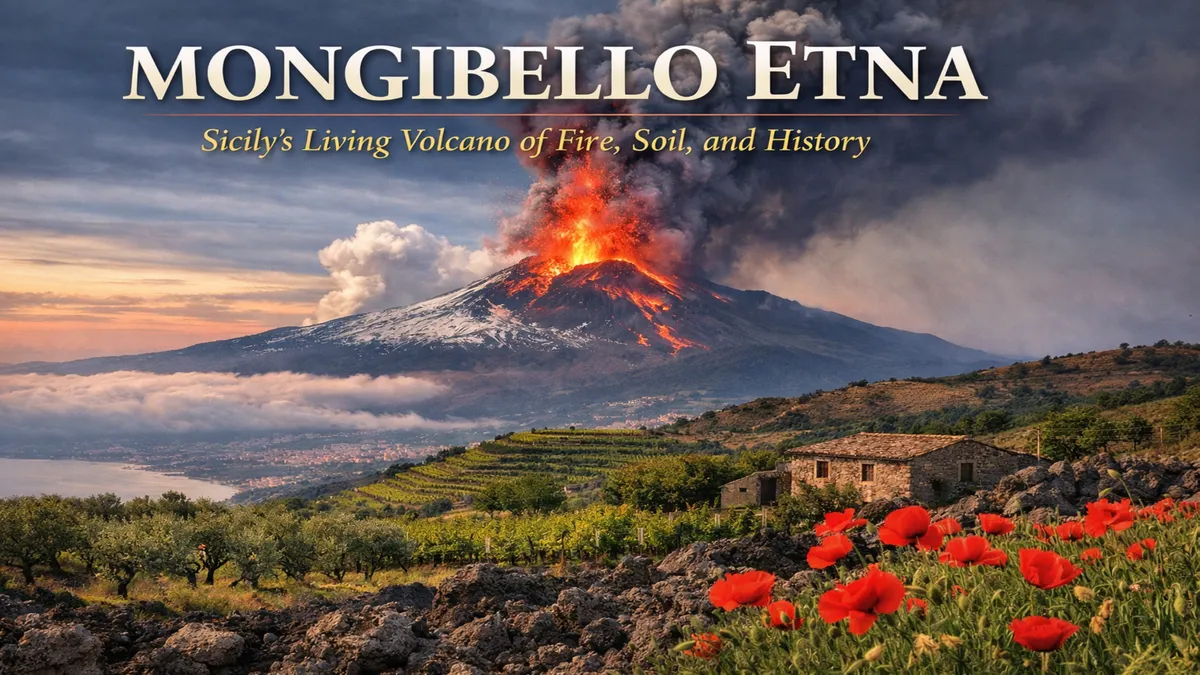

Mongibello, better known to the wider world as Mount Etna, is not simply a volcano rising above Sicily; it is a living system that has shaped land, language, agriculture, and imagination for thousands of years. The name “Mongibello” itself reflects the island’s layered past, combining the Latin mons and the Arabic jabal, both meaning mountain, into a single word that means “mountain-mountain.” This linguistic doubling mirrors Etna’s physical and symbolic enormity. It dominates eastern Sicily’s skyline, influences its climate and soil, and defines the rhythms of life for the communities settled around its slopes.

From a scientific perspective, Etna is Europe’s most active volcano and one of the most continuously observed on Earth. Its frequent eruptions, shifting summit height, and ever-changing crater system make it a natural laboratory for volcanologists. From a cultural perspective, it is a presence that cannot be ignored: feared, revered, and woven into myth, poetry, and daily speech. Farmers depend on its fertile volcanic soils even as they live with the constant possibility of lava flows and ash fall. Tourists climb its flanks to witness landscapes that feel both ancient and newly formed.

To understand Mongibello is therefore to understand a relationship between humans and geological time, between short human lives and a mountain that grows and reshapes itself over millennia. This article follows that relationship across science, history, and culture, showing how Etna is at once a hazard, a resource, a symbol, and a teacher.

The Mountain With Many Names

The volcano’s multiple names reveal its deep integration into different civilizations. The Greek “Aitna,” associated with burning and fire, emphasized the volcano’s eruptive nature. Roman writers adopted and adapted this name, while Arab rulers introduced the word jabal, meaning mountain, which later merged with Latin mons to form “Mongibello.” Local Sicilian dialects transformed it further into forms like “Mungibeddu,” while everyday speech often reduces it simply to “the mountain.”

Each name encodes a different way of seeing the volcano. To ancient peoples it was the forge of gods or the prison of giants. To medieval communities it was a divine sign or a natural menace. To modern scientists it is a complex system of magma chambers, vents, and tectonic interactions. To farmers and winemakers it is soil, water, and risk combined. The volcano’s many names are therefore not synonyms but perspectives, layered like the lava flows that built the mountain itself.

Geological Structure and Activity

Etna is a stratovolcano formed through hundreds of thousands of years of eruptions, collapses, and rebuilding. Its base spans a wide area of eastern Sicily, and its summit height changes over time as eruptions add material or explosions remove it. The volcano contains several summit craters and numerous flank vents, allowing eruptions to occur not only at the top but along its sides, sometimes closer to inhabited areas.

One of Etna’s most striking features is the Valle del Bove, a vast depression on its eastern flank created by ancient collapses. This scar records violent episodes in the volcano’s past and provides scientists with visible layers of lava and ash that function like pages in a geological book. By studying these layers, researchers reconstruct eruption histories, magma composition changes, and shifts in eruptive style.

The volcano’s activity is driven by its tectonic setting near the boundary between the African and Eurasian plates. Magma rises through fractures in the crust, accumulating in chambers before being released through eruptions that can range from gentle lava flows to explosive ash plumes. This variability is what makes Etna both fascinating and challenging to monitor.

Historical Eruptions and Human Memory

Human records of Etna’s eruptions stretch back more than two millennia, making it one of the longest continuously documented volcanoes in the world. Ancient historians, medieval chroniclers, and modern scientists have all described its activity. Among the most famous eruptions was the one in 1669, when lava flows advanced toward and into the city of Catania, destroying villages and reshaping the coastline.

These events left deep marks not only on the landscape but on collective memory. Stories of fleeing lava, ash-darkened skies, and prayers for protection became part of local tradition. At the same time, people returned again and again to the volcano’s slopes, rebuilding homes and fields on land that had been buried only decades earlier. This cycle of destruction and renewal is central to Etna’s human history.

Cultural Meanings and Myth

Long before modern geology explained magma and tectonics, people turned to myth to understand Etna. Greek stories placed the forge of Hephaestus beneath the mountain, explaining fire and smoke as the work of a divine blacksmith. Other legends imagined the giant Typhon imprisoned under the volcano, his struggles causing eruptions and earthquakes.

These myths did more than entertain; they provided frameworks for living with uncertainty. By personifying the volcano, people could relate to it, fear it, respect it, and attempt to negotiate with it through ritual and prayer. Even today, while science provides different explanations, the emotional and symbolic power of Etna remains strong in art, literature, and local identity.

Scientific Monitoring and Research

Modern technology has transformed Etna into one of the best-monitored volcanoes on Earth. Networks of seismometers detect earthquakes that signal magma movement. Gas sensors measure sulfur dioxide and other emissions that change before eruptions. Satellite imagery tracks ground deformation as magma accumulates beneath the surface.

This monitoring does not eliminate risk, but it reduces uncertainty. It allows authorities to close areas, redirect tourists, and warn communities when activity increases. Etna has therefore become a testing ground for volcanic hazard management, contributing knowledge that helps protect people not only in Sicily but near volcanoes worldwide.

Expert observers often note that Etna’s value lies not only in what it threatens but in what it teaches. Its frequent but often moderate eruptions provide opportunities to study processes that are hidden or catastrophic elsewhere. In this sense, Mongibello is both a natural hazard and a scientific gift.

Agriculture, Economy, and Daily Life

Volcanic soil is among the most fertile on Earth, and Etna’s slopes support vineyards, orchards, and farms that produce some of Sicily’s most prized foods and wines. Minerals from ash and lava enrich the soil, while the mountain’s elevation creates microclimates suitable for diverse crops.

This fertility draws people close to danger. Towns and villages cluster along Etna’s flanks because the land is productive and beautiful. Tourism adds another layer, as visitors are drawn by the chance to walk on recent lava flows, ski on volcanic slopes, or gaze into steaming craters. The local economy thus depends on the very forces that also threaten it, creating a delicate balance between opportunity and risk.

Comparative Context

| Volcano | Location | Activity Level | Cultural Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Etna | Sicily, Italy | Very high | Deeply embedded in daily life |

| Vesuvius | Campania, Italy | Low to moderate | Historical catastrophe symbol |

| Teide | Canary Islands, Spain | Low | National park and landmark |

| Aspect | Benefit | Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Soil fertility | High agricultural productivity | Settlement near hazard zones |

| Tourism | Economic growth | Exposure of visitors to danger |

| Scientific study | Advances in volcanology | Dependence on monitoring accuracy |

Takeaways

- Mongibello is the Sicilian name for Mount Etna, reflecting linguistic layers of history.

- Etna is Europe’s most active volcano and one of the longest recorded.

- Its eruptions shape land, culture, and scientific understanding simultaneously.

- Myths and modern science offer different but complementary ways of interpreting the mountain.

- Life on Etna’s slopes is a continuous negotiation between fertility and danger.

Conclusion

Mongibello–Etna stands as a reminder that humanity does not live apart from nature but within it, subject to its rhythms and transformations. The volcano’s fire destroys and creates, threatens and nourishes, frightens and inspires. Over centuries, people have responded with myth, with science, with resilience, and with a willingness to rebuild. In doing so, they have turned a volatile mountain into a center of culture, knowledge, and life.

Etna teaches that coexistence with powerful natural forces is not a problem to be solved once and for all but a relationship to be managed continuously. It asks for attention, respect, and humility. In return, it offers insight into the deep workings of the Earth and a landscape unlike any other. Mongibello is therefore not just a volcano; it is a dialogue between fire and humanity that has been ongoing for thousands of years and will continue as long as the mountain breathes.

FAQs

What does Mongibello mean?

It combines Latin and Arabic words for mountain, meaning “mountain-mountain,” reflecting Sicily’s layered history.

Why is Etna so active?

It lies near a tectonic boundary where magma is continually generated and rises toward the surface.

Is it safe to live near Etna?

It carries risk, but monitoring and planning reduce danger and allow communities to coexist with it.

Why is Etna important to science?

Its frequent activity and accessibility make it ideal for studying volcanic processes.

How does Etna affect agriculture?

Its ash and lava create fertile soils that support rich farming and vineyards.

References

- Britannica Editors. (2025). Mount Etna—Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Mount-Etna Encyclopedia Britannica

- Mount Etna. (n.d.). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1427/ UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- Topspotmagazine. (2025, November 1). Mongibello Etna: Why Sicily’s Giant Has Two Names. https://topspotmagazine.co.uk/mongibello-etna/ Top Spot Magazine

- Visit Sicily. (n.d.). Mount Etna information. https://www.visitsicily.info/en/attrazione/mount-etna/ visitsicily.info

- Smart Education Unesco Sicilia. (n.d.). The different names of the “Muntagna”. https://www.smarteducationunescosicilia.it/en/monte-etna/the-different-names-of-the-muntagna-2/ smarteducationunescosicilia.it