Recyclatanteil is a simple word with a complicated meaning. It refers to the proportion of recycled material used in the production of a product compared to the total material input. In a bottle made from 30 percent recycled plastic and 70 percent virgin plastic, the Recyclatanteil is 30 percent. This number has become one of the most important indicators in modern sustainability policy because it measures not how much waste is collected, but how much of that waste actually returns to the economy.

This distinction matters. Recycling rates often give a comforting picture of environmental progress, but they can hide the reality that collected materials are frequently exported, incinerated, or downcycled into low-value uses. Recyclatanteil shifts attention away from waste bins and toward factories, supply contracts, and production lines. It asks whether recycled material is genuinely replacing virgin resources or simply moving through the system without changing it.

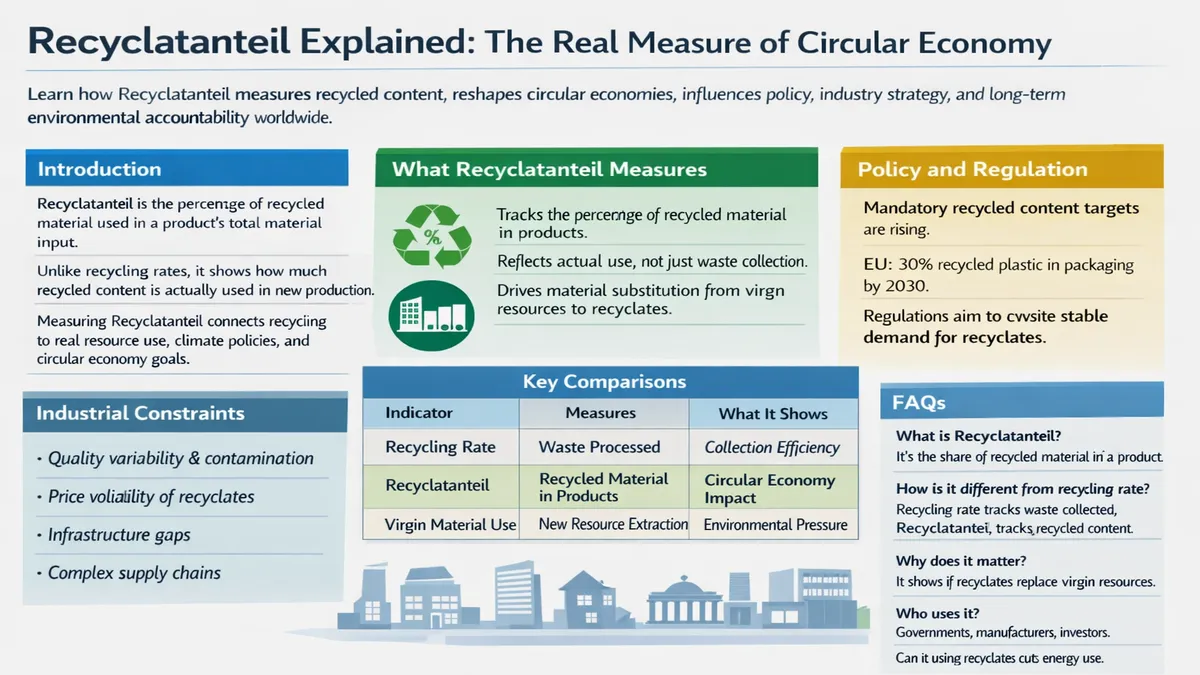

Across Europe and increasingly in global markets, Recyclatanteil has become central to circular economy strategies. Governments set recycled content targets. Companies publish recycled content disclosures. Investors track recycled content as a sign of long-term resource resilience. The metric now connects environmental goals, industrial competitiveness, and climate policy in a way few other sustainability indicators do.

Understanding Recyclatanteil therefore means understanding not only recycling but the deeper economic transition away from extraction and toward regeneration. It reveals how far industries have moved from a linear model of take-make-waste toward one that treats materials as assets that circulate, retain value, and reduce environmental harm.

What Recyclatanteil Measures

Recyclatanteil measures the share of recycled material that is used as input in manufacturing. It does not measure how much waste is collected or processed, but how much recycled material is actually incorporated into new products.

This makes it a fundamentally different indicator from recycling rates. A country can have a high recycling rate and a low Recyclatanteil if recycled material is exported, stockpiled, or used only in niche applications. A product can be marketed as recyclable while still containing zero recycled content. Recyclatanteil exposes that difference.

By focusing on material use rather than waste handling, the metric reflects economic reality. Manufacturers must be willing and able to buy recycled material. Recyclers must be able to supply material that meets quality standards. Policymakers must align regulations so that recycled content is not only encouraged but viable.

Recyclatanteil therefore operates at the intersection of engineering, economics, and governance. It measures not environmental intention but material substitution — whether recycled inputs are actually replacing virgin ones.

Policy and Regulation

In the European Union, recycled content targets have become a central part of sustainability regulation. Policymakers argue that without mandatory recycled content requirements, recycling systems struggle to find stable demand. Waste is collected, but recyclates lack buyers.

Targets such as a 30 percent recycled content requirement in plastic packaging by 2030 are designed to create guaranteed markets for recycled materials. This encourages investment in sorting, cleaning, and processing infrastructure while also signaling to manufacturers that recycled inputs will become the norm rather than the exception.

Recyclatanteil is thus not only a measurement tool but a policy instrument. It transforms sustainability from a voluntary commitment into a material requirement embedded in production standards.

Recycling Rates Versus Recycled Content

The difference between recycling rates and recycled content explains many contradictions in sustainability reporting. Recycling rates measure waste flows. Recyclatanteil measures material flows.

A system can perform well in waste collection while failing in material reintegration. This disconnect is why plastic recycling rates can rise while virgin plastic production continues to increase. Without high Recyclatanteil, recycling becomes an end-of-pipe solution rather than a resource strategy.

The metric also clarifies public misunderstandings. Consumers may believe that placing an item in a recycling bin completes a circular process. In reality, the circular process only completes when recycled material replaces virgin material in new production.

| Indicator | Measures | What It Shows |

|---|---|---|

| Recycling rate | Waste collected and processed | Effectiveness of waste systems |

| Recyclatanteil | Recycled material used in products | Effectiveness of circular economy |

| Virgin material share | New resource extraction | Environmental pressure |

Industrial Constraints

Industries face real challenges in increasing Recyclatanteil. Recycled materials often vary in quality, color, and composition. Contamination can limit their use in sensitive applications like food packaging, medical devices, or electronics.

Manufacturers are also sensitive to price volatility. Virgin materials benefit from established supply chains and economies of scale. Recycled materials depend on waste streams that fluctuate with consumer behavior, regulations, and market demand.

As a result, companies increasingly treat recycled material contracts as strategic resources. Securing stable access to high-quality recyclates has become part of long-term risk management, similar to energy sourcing or rare-earth procurement.

| Constraint | Impact on Recyclatanteil |

|---|---|

| Quality variability | Limits technical usability |

| Contamination | Restricts applications |

| Price volatility | Discourages long-term reliance |

| Infrastructure gaps | Reduces supply reliability |

Expert Perspectives

“Recycled content is where sustainability becomes industrial reality,” one sustainability policy analyst explains. “It is the moment where environmental goals meet production constraints and market logic.”

A materials scientist adds, “Recyclates must perform as reliably as virgin materials if they are to replace them. Innovation in sorting, cleaning, and chemical recycling is crucial.”

An industry strategist observes, “Companies that fail to integrate recycled materials into their supply chains risk regulatory exposure and resource insecurity in the future.”

These perspectives reveal that Recyclatanteil is not a branding metric but a structural one. It measures the depth of transformation rather than the surface of commitment.

Takeaways

- Recyclatanteil measures recycled content, not recycling activity

- It reflects whether materials truly circulate back into production

- Policies increasingly mandate minimum recycled content levels

- Industrial barriers remain technical, economic, and logistical

- Recyclatanteil links sustainability with competitiveness and resilience

Conclusion

Recyclatanteil is a quiet number with loud implications. It moves sustainability from aspiration to accountability by showing whether recycling systems actually change production practices. It reveals whether waste becomes a resource or remains a byproduct.

As climate pressures, resource scarcity, and regulatory demands intensify, this metric will only grow in importance. It exposes greenwashing, rewards real innovation, and anchors environmental progress in physical material flows rather than symbolic gestures.

In the end, Recyclatanteil is not just about recycling. It is about redefining how economies treat matter itself — not as something to extract, discard, and replace, but as something to preserve, circulate, and reuse.

FAQs

What is Recyclatanteil

It is the percentage of recycled material used in a product’s total material input.

How is it different from recycling rate

Recycling rate measures waste collection, Recyclatanteil measures recycled material usage.

Why is it important

It shows whether recycling actually replaces virgin resource extraction.

Who uses this metric

Governments, manufacturers, investors, and sustainability analysts.

Can it reduce emissions

Yes, because recycled materials often require less energy than virgin ones.