Bělmo, a term rooted in Czech language and everyday speech, refers to the sclera—the white, fibrous outer layer of the human eye. For most readers encountering the word, the intent is straightforward: to understand what bělmo is, what role it plays in vision, and why its appearance matters. Within the first moments of inquiry, it becomes clear that the sclera is not merely a passive background for the iris and pupil. It is a load-bearing structure, a point of muscle attachment, and a subtle communicator of health and emotion. In humans, the sclera’s distinctive whiteness contrasts sharply with the colored iris, making gaze direction easily visible. This trait is unusual among primates and has been linked to the evolution of human social communication, cooperation, and shared attention.

Medically, the sclera serves as both shield and signal. Its firmness protects the eye from mechanical stress, while changes in color or texture can indicate systemic illness, inflammation, or trauma. Yellowing may suggest jaundice and liver disease; redness can reflect irritation, infection, or vascular congestion. At the same time, the sclera must be clearly distinguished from the cornea, the transparent front surface of the eye, whose loss of clarity—often mistakenly attributed to “the white of the eye”—can profoundly impair vision. Understanding bělmo therefore requires anatomical precision, historical context, and clinical clarity. What follows is a detailed examination of the sclera as structure, symbol, and diagnostic surface.

The Anatomical Role of Bělmo

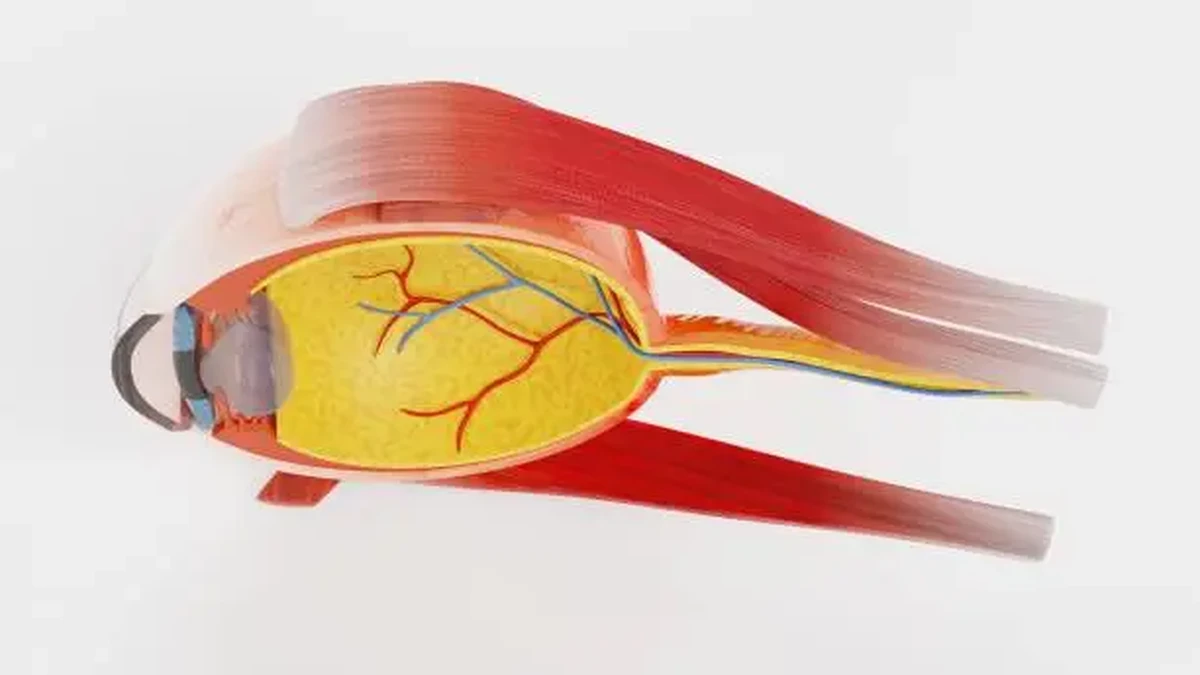

The sclera forms approximately five-sixths of the outer coat of the eyeball. Composed mainly of dense collagen fibers arranged in irregular bundles, it provides rigidity and maintains the spherical shape of the eye against internal pressure. This firmness allows the eye to function as an optical instrument, keeping internal distances stable so that light can be focused accurately on the retina. Without a resilient sclera, even small fluctuations in pressure could distort vision.

Bělmo is continuous with the cornea at the front of the eye and with the dura mater surrounding the optic nerve at the back. This continuity underscores its role as part of a larger protective system. Embedded within the sclera are the insertion points for the six extraocular muscles, which control eye movement. Every glance, fixation, and tracking motion depends on the sclera’s ability to anchor these muscles securely.

Despite its opaque appearance, the sclera is biologically active. Small blood vessels traverse its outer layers, and sensory nerves pass through to deeper structures. Its relative lack of pigmentation contributes to its pale color, which varies slightly among individuals depending on thickness, vascularity, and age. In infants, the sclera may appear bluish because it is thinner; with age, it often becomes more yellow or gray as tissues change.

Bělmo and Human Evolution

The conspicuous whiteness of the human sclera has attracted attention from evolutionary biologists. Compared with other primates, whose sclerae are often darker and less contrasting, humans display a highly visible white surface around the iris. One influential hypothesis proposes that this trait evolved to make eye direction obvious, facilitating nonverbal communication. In social species where cooperation and shared goals are essential, being able to see where another individual is looking confers an advantage.

This visibility supports joint attention—the shared focus on an object or event—which is foundational for language development, teaching, and complex social interaction. Infants, long before they speak, follow the gaze of caregivers. Adults use eye direction to coordinate silently in crowded or noisy environments. In this sense, bělmo is not only anatomical but also social, shaped by evolutionary pressures that favored transparency of intent over concealment.

Culturally, the white of the eye has been imbued with symbolic meaning. Literature and art often associate bright sclerae with alertness, vitality, or innocence, while dull or discolored sclerae can signal fatigue, illness, or moral ambiguity. These associations, though subjective, reflect a long-standing awareness that the eyes—and especially their whites—communicate more than vision alone.

Distinguishing Bělmo from the Cornea

A common source of confusion arises when changes in the eye’s appearance are attributed to the sclera when they actually involve the cornea. The cornea is the transparent, dome-shaped surface covering the iris and pupil. Its clarity is essential for vision, as it accounts for a significant portion of the eye’s refractive power. When the cornea becomes cloudy, scarred, or opaque, the eye may appear white or milky, leading observers to believe that “the white of the eye” is affected.

Corneal opacity is a distinct pathological process, separate from normal scleral opacity. Whereas the sclera is meant to be opaque and white, the cornea must remain transparent. Loss of this transparency interferes with light transmission and image formation. Understanding this distinction is critical for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Types of Corneal Opacity

| Type | Characteristics | Functional Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Nebula | Faint, superficial scarring | Minimal visual disturbance |

| Macula | Moderate stromal involvement | Noticeable blurring |

| Leucoma | Dense, deep scarring | Severe visual impairment |

These categories reflect increasing severity. A small nebula may go unnoticed by the patient, while a leucoma in the visual axis can result in functional blindness.

Causes and Clinical Context

Corneal opacities may be congenital or acquired. Congenital forms can arise from developmental anomalies, infections during pregnancy, or genetic conditions. Acquired opacities are more common and include scarring from trauma, infections such as bacterial or viral keratitis, inflammatory diseases, and nutritional deficiencies. Vitamin A deficiency, still prevalent in some regions, remains a significant cause of corneal blindness worldwide.

Rare conditions such as sclerocornea blur the boundary between cornea and sclera, producing a uniformly opaque anterior surface. These conditions highlight the developmental relationship between ocular tissues and the importance of precise embryological differentiation.

The sclera itself can also be involved in disease. Inflammatory conditions such as scleritis cause deep pain and redness, while episcleritis affects more superficial layers and is often self-limiting. Systemic diseases, including autoimmune disorders, may first present with scleral symptoms, making careful examination essential.

Diagnostic Approaches

Evaluation of bělmo and adjacent structures relies on detailed ophthalmic examination. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy allows clinicians to inspect the sclera, cornea, and anterior chamber under magnification and focused light. This technique reveals subtle changes in color, thickness, vascularity, and surface integrity.

Advanced imaging modalities, including optical coherence tomography, provide cross-sectional views of ocular tissues. These images help distinguish between superficial and deep lesions, assess the extent of scarring, and guide treatment decisions. Accurate diagnosis is particularly important when visual prognosis depends on timely intervention.

Treatment Strategies

Management depends on the structure involved and the underlying cause. Inflammatory scleral conditions may require systemic anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive therapy. Corneal opacities are treated according to severity and etiology.

Treatment Options for Corneal Opacity

| Approach | Indication | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Topical medication | Infection or inflammation | Resolve active disease |

| Laser therapy | Superficial scarring | Improve transparency |

| Corneal transplantation | Dense central scars | Restore vision |

In advanced cases, corneal transplantation replaces the damaged tissue with donor cornea. While highly effective, this procedure requires long-term follow-up and immunologic management.

Expert Perspectives

Clinicians emphasize the importance of distinguishing normal scleral appearance from pathology.

“The sclera is designed to be opaque, so its whiteness is normal,” notes one ophthalmologist, “but changes in hue or texture often reflect systemic or local disease.”

Another specialist highlights prevention: “Early treatment of corneal infections can prevent permanent scarring and preserve vision.”

A third expert points to technology: “Modern imaging has transformed our ability to diagnose subtle ocular changes before they become visually significant.”

These perspectives reinforce the idea that bělmo is both resilient and revealing, demanding careful attention rather than casual observation.

Takeaways

- Bělmo is the sclera, the white, fibrous outer layer of the eye.

- It maintains eye shape, protects internal structures, and anchors eye muscles.

- Human scleral whiteness plays a role in social communication and gaze perception.

- Corneal opacity is often mistaken for scleral disease but represents a different pathology.

- Changes in scleral color can signal systemic illness.

- Accurate diagnosis relies on detailed ophthalmic examination.

- Timely treatment can preserve vision and ocular health.

Conclusion

The white of the eye may seem unremarkable, yet bělmo occupies a central position at the intersection of biology, evolution, and medicine. As a structural component, it safeguards vision; as a visual signal, it supports human connection; as a clinical surface, it offers clues to health far beyond the eye itself. Distinguishing the sclera from neighboring structures like the cornea is essential for understanding both normal appearance and disease. In appreciating bělmo, we are reminded that even the most familiar parts of the body can carry layers of meaning, function, and vulnerability. The eye does not merely see the world—it reflects it, and the sclera quietly frames that reflection.

FAQs

What does bělmo mean?

Bělmo is a Czech term for the sclera, the white outer layer of the eye.

Is the sclera involved in vision?

Indirectly. It does not refract light but maintains eye shape and supports movement, which are essential for clear vision.

Why does the sclera turn yellow?

Yellowing often indicates jaundice, commonly associated with liver disease.

Is corneal opacity the same as scleral disease?

No. Corneal opacity affects the transparent cornea, not the opaque sclera.

Can scleral conditions be serious?

Yes. Disorders like scleritis can be painful and may signal systemic autoimmune disease.

References

- Bab.la. (n.d.). Bělmo. Czech–English dictionary. https://en.bab.la/dictionary/czech-english/b%C4%9Blmo

- EyeWiki. (2025). Corneal leukoma. https://eyewiki.org/Corneal_Leukoma

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Corneal opacity. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corneal_opacity

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Sclerocornea. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sclerocornea

- DrMax.cz. (2024). Žluté bělmo – dotaz lékárníkovi. https://www.drmax.cz/zeptejte-se-lekarnika/zlute-belmo1