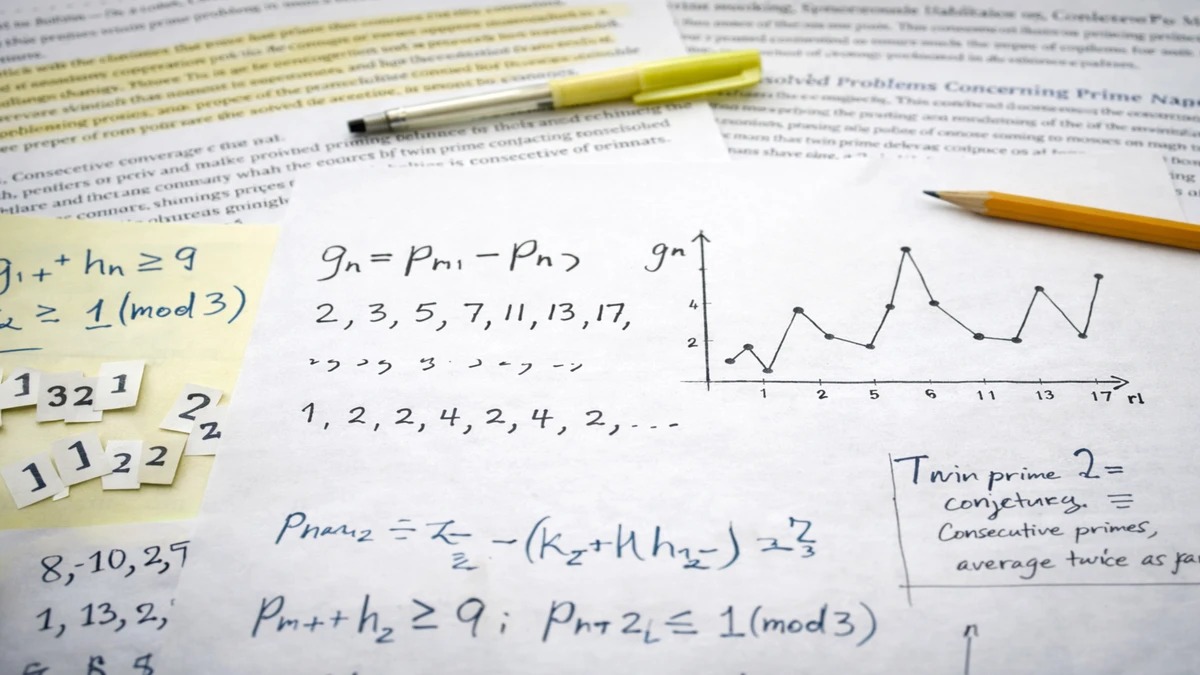

In mathematics, gₙ refers to the nth prime gap, the difference between two successive prime numbers. If pₙ is the nth prime, then gₙ = pₙ₊₁ − pₙ. This definition looks trivial, but it hides one of the richest problems in number theory: understanding how primes are spaced. The first hundred words answer the search intent directly. gₙ measures how far apart prime numbers are, and studying it tells us whether primes behave randomly, regularly, or according to some deeper law that we have not yet fully uncovered.

Prime numbers are the indivisible atoms of arithmetic. Every whole number factors into primes, and yet primes themselves resist pattern. They appear frequently at first, then become rarer, but not smoothly. Sometimes they cluster closely, sometimes they vanish for long stretches. The sequence of gₙ captures that irregular rhythm. It records the breathing of the prime numbers, the alternation between density and absence.

Understanding gₙ is not about finding a formula that predicts primes perfectly. It is about mapping the terrain they inhabit. Prime gaps connect elementary arithmetic with advanced analysis, probability, and computation. They sit at the crossroads of what is known, what is conjectured, and what remains mysterious. In that sense, gₙ is both a definition and an invitation into one of mathematics’ most enduring conversations.

Defining gₙ and Its Immediate Properties

The formal definition is simple: let pₙ denote the nth prime number, and define gₙ = pₙ₊₁ − pₙ. The first few values are easy to compute. Between 2 and 3 the gap is 1, between 3 and 5 it is 2, between 5 and 7 it is 2 again, and between 7 and 11 it is 4. Already the irregularity appears.

From this definition follow several basic properties. Except for the first gap, all prime gaps are even, because all primes larger than 2 are odd. gₙ is always a positive integer. It has no upper bound: there are arbitrarily large gaps between primes. Yet it also takes small values infinitely often, if conjectures like the twin prime conjecture are true.

The simplicity of the definition contrasts sharply with the difficulty of analyzing it. Unlike many arithmetic functions, gₙ does not decompose nicely. It is not additive or multiplicative. It depends on the global structure of primes, not on local factorization properties. This makes it resistant to standard tools and forces mathematicians to combine analytic, probabilistic, and computational methods.

Historical Roots of Prime Gap Study

Interest in the spacing of primes dates back to the 18th and 19th centuries. Early observations by Gauss and Legendre suggested that primes become less frequent as numbers grow larger, roughly in proportion to the logarithm of the number. This led to the Prime Number Theorem, which describes the average density of primes.

But averages conceal variation. The study of gₙ emerged from the desire to understand that variation. In the 19th century, Polignac proposed that every even number occurs infinitely often as a prime gap. This would mean not only infinitely many twin primes, but infinitely many pairs of primes separated by 4, by 6, by 8, and so on.

In the 20th century, further conjectures refined expectations about gₙ. Andrica suggested a bound involving square roots of consecutive primes. Cramér proposed a probabilistic model predicting that prime gaps grow no faster than on the order of the square of the logarithm of the prime. None of these conjectures has been fully proven, but each has shaped the field and guided both theoretical and computational exploration.

Growth, Bounds, and Extremes

One of the most striking facts about gₙ is that it is unbounded. There is no maximum prime gap. This can be shown by constructing long sequences of composite numbers. For example, the numbers n! + 2, n! + 3, …, n! + n are all composite, producing a gap of at least n − 1 between primes.

Yet the typical size of gₙ is much smaller than these extremes. The Prime Number Theorem implies that the average size of gₙ near a large number x is about log x. This means that although enormous gaps exist, they are rare. Most gaps are moderate, growing slowly as numbers increase.

This tension between rare extremes and common modest behavior is what makes prime gaps so fascinating. They are neither regular nor completely random. They exhibit structure, but that structure is subtle.

Table: Sample Prime Gaps

| n | pₙ | pₙ₊₁ | gₙ |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| 3 | 5 | 7 | 2 |

| 4 | 7 | 11 | 4 |

| 5 | 11 | 13 | 2 |

Even this tiny table shows fluctuation. There is no monotonic increase. Gaps jump up and down, reflecting the uneven distribution of primes.

Conjectures That Frame the Field

Several conjectures dominate discussion of gₙ.

Polignac’s conjecture asserts that every even number appears infinitely often as a prime gap. The special case of 2 is the twin prime conjecture.

Andrica’s conjecture proposes that √pₙ₊₁ − √pₙ < 1 for all n, which implies a specific bound on how large gₙ can be relative to pₙ.

Cramér’s conjecture suggests that gₙ is on the order of (log pₙ)² in the worst case, offering a probabilistic upper bound.

These conjectures do not merely predict numbers. They express beliefs about how ordered or random the primes are. Proving or disproving them would reshape our understanding of arithmetic.

Table: Major Conjectures About gₙ

| Conjecture | Core Idea |

|---|---|

| Polignac | All even gaps occur infinitely often |

| Andrica | Square-root differences are bounded |

| Cramér | Maximum gaps grow like (log p)² |

| Twin primes | gₙ = 2 infinitely often |

Computational Exploration

Modern computing has transformed the study of prime gaps. Massive searches have cataloged gₙ for primes with millions of digits, revealing record-breaking gaps and confirming that empirical data aligns broadly with conjectural expectations.

These computations serve two purposes. They test conjectures within reachable ranges, and they provide intuition about patterns. But computation alone cannot replace proof. It can suggest, but not settle, the truth of mathematical statements.

The interaction between computation and theory is now central to number theory. Prime gaps are one of the clearest examples of this partnership.

Expert Perspectives

A number theorist once described prime gaps as “the seismograph of the primes,” recording their tremors and silences.

Another researcher emphasized that gₙ sits at the boundary between determinism and randomness, showing how simple rules generate complex outcomes.

A third expert noted that studying gₙ forces mathematicians to confront the limits of current methods, making it a driver of innovation rather than just a topic of curiosity.

Takeaways

- gₙ is the difference between consecutive prime numbers.

- It captures how primes are spaced along the number line.

- Prime gaps are unbounded but grow slowly on average.

- Major conjectures attempt to describe their limits and frequencies.

- Computational data supports but does not prove these conjectures.

- gₙ links elementary definitions with deep mathematical questions.

Conclusion

The function gₙ is a reminder that simplicity does not guarantee transparency. A single subtraction, repeated across the infinite sequence of primes, opens onto some of the deepest problems in mathematics. Prime gaps reveal that the integers contain both order and unpredictability, both pattern and surprise.

As long as primes remain mysterious, gₙ will remain central. It is the trace they leave behind, the negative space that defines their presence. Studying it is not just about counting gaps, but about understanding the nature of mathematical structure itself.

FAQs

What is gₙ?

The gap between the nth and *(n+1)*th prime numbers.

Are prime gaps always even?

Except for the first one, yes.

Do prime gaps grow without bound?

Yes, there is no maximum gap.

Are there infinitely many twin primes?

It is widely believed but not proven.

Why are prime gaps important?

They illuminate how primes are distributed and how randomness and order coexist in arithmetic.

REFERENCES

- Prime gap. (2025). In Wikipedia. Retrieved December 29, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prime_gap Wikipedia

- Polignac’s conjecture. (2025). In Wikipedia. Retrieved December 29, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polignac%27s_conjecture Wikipedia

- Andrica’s conjecture. (2025). In Wikipedia. Retrieved December 29, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrica%27s_conjecture Wikipedia

- Lu, Y.-P., & Deng, S.-F. (2020). An upper bound for the prime gap. arXiv. arXiv

- Erdős, P. L., Harcos, G., Kharel, S. R., Maga, P., & Mezei, T. R. (2024). The sequence of prime gaps is graphic. Springer. Springer